Six years after petitioning the U.S. government for tariffs to make its products more competitive, U.S.-based Suniva has revealed plans to commence 1 GW of cell manufacturing by spring 2024, followed by an additional 2.5 GW expansion.

We now have verification that solar module tariffs are morally, ethically, spiritually, physically, positively, absolutely, undeniably and reliably dead! Suniva has announced plans to restart its solar cell manufacturing. This announcement comes after years of the company’s lobbying to restrict global solar panel imports into the U.S.

Remarkably, Suniva did not resume production even after succeeding in securing tariffs in February 2018. Nor did they make any moves during the record-breaking years of 2020 and 2021 for solar deployment. But in 2023, the company finally broke its silence.

Cristiano Amoruso, Suniva’s CEO and Board member, stated in a press release:

The Inflation Reduction Act and its Domestic Content provisions, as issued, provide a strong foundation for continued solar cell technology development and manufacturing in the United States.

Suniva plans to reactivate and expand its Norcross, Georgia facility. The company aims to kick off production by spring 2024 with a 1 GW capacity, eventually scaling up to 2.5 GW annually. Earlier this year, Suniva secured $110 million in financing from Orion Infrastructure Capital, which also partnered with Heliene for a $170 million manufacturing expansion.

The case for carrots over sticks

Though the IRA appears to have fueled the current U.S. solar manufacturing boom, it’s not the only factor. Existing tariffs, and import restrictions, have inflated prices in the domestic solar module market. However, historical data provides valuable context.

Despite past tariffs, the U.S. solar market expanded. The tariffs first imposed in 2012 and 2014 by the Obama administration aimed to counter economic espionage by Chinese military hackers against SolarWorld, the theft of monoPERC technology, and the dumping of solar cells.

According to data from Clean Energy Associates, U.S. solar manufacturing continued to decline after tariffs were introduced, but saw a modest uptick later. Peaking in 2019, 19.8% of all U.S. solar installations utilized domestically produced modules, according to the Coalition for a Prosperous America.

In that year, the U.S. deployed 13.3 GW of solar panels, with about 2.6 GW sourced from domestic manufacturers that had approximately 8 GW of available capacity. However, in the following two years, as the U.S. market rebounded and set annual records, the share of modules manufactured domestically started to decline relative to the total number of modules installed.

When another tariff petition surfaced in 2021, this time from an ‘anonymous’ company, no new manufacturers announced plans.

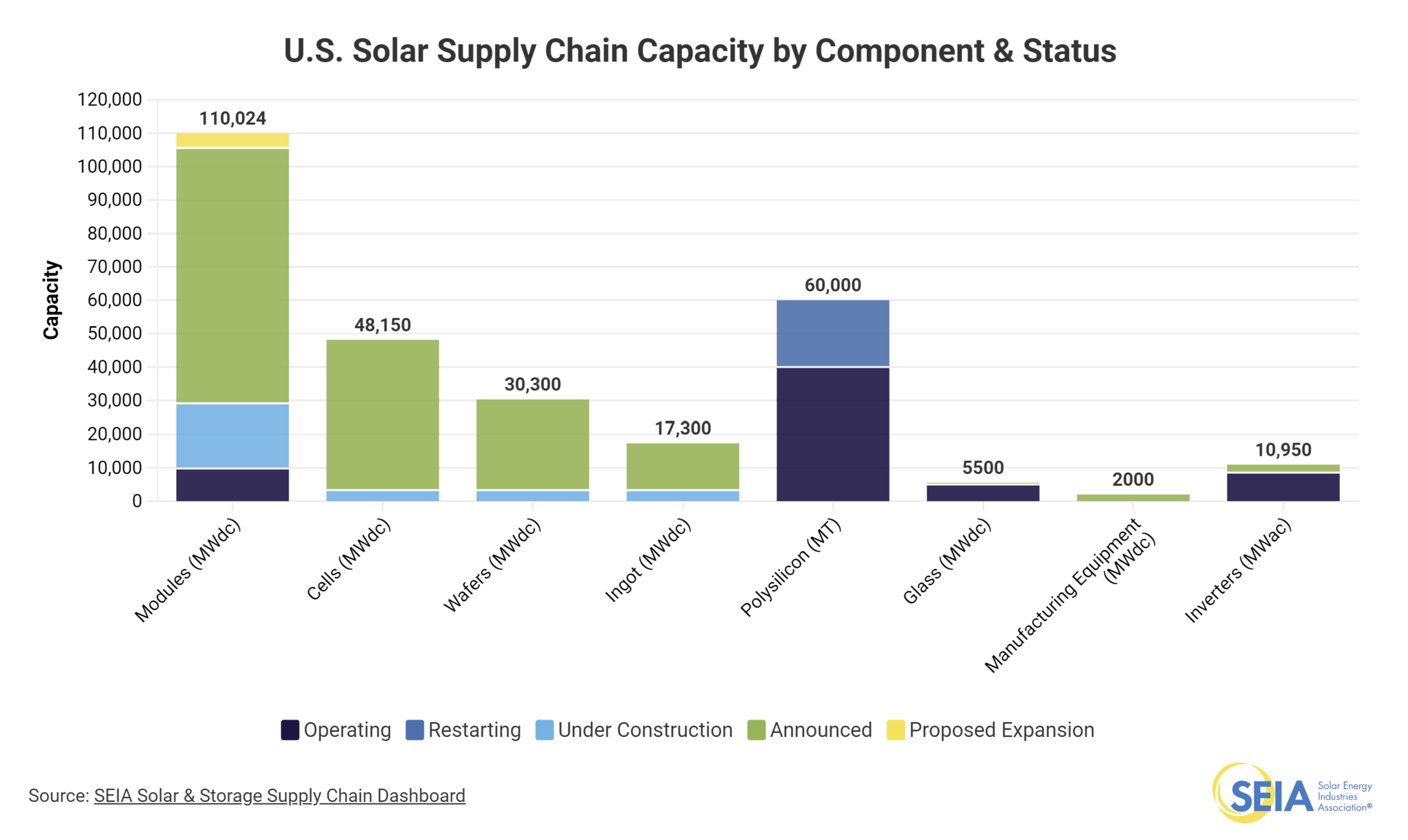

However, following the enactment of the IRA, capacity projections have skyrocketed, leading some analysts to speculate that the U.S. could become a solar panel exporter. According to the Solar Energy Industries of America, U.S. manufacturing capacity has soared from 8.4 GW in 2022 to over 110 GW, marking an impressive 1200% growth in about a year.

In just 14 months since the IRA was signed, the U.S. shifted from meeting less than 20% of its module demand domestically to potentially satisfying several hundred percent of future demand through domestic module manufacturers.

The manufacturing surge isn’t limited to the U.S.; India is also experiencing a boom. By first instituting import duties on solar panels and cells, especially those from neighboring China, and then by offering state-provided production incentives, India projects 100 GW of solar manufacturing capacity by 2026.

It’s worth noting that import duties alone weren’t the fuel for India’s manufacturing growth. The true catalyst came in the form of state-provided solar production incentives. With these incentives, the country now estimates that 100 GW of solar manufacturing capacity could be operational by 2026.

As Europe confronts its own dilemmas about becoming a solar module manufacturer, research indicates that solar panel import tariffs, possibly coupled with economic recession and technological limitations of the time, led to the loss of tens of thousands of jobs in Germany.

In the U.S., another looming tariff case merits attention: the anticircumvention case set to extend the 2012 and 2014 solar cell tariffs to Southeast Asian countries, which have become manufacturing hubs for Chinese companies.

Several questions arise for the United States: Is the Inflation Reduction Act sufficient? Should existing tariffs remain in place to set a price floor? Should the U.S. continue restricting polysilicon imports from geopolitically complex regions?

While all of these questions call for thorough analysis and legislative action, the issue of the effectiveness of tariffs in stimulating manufacturing capacity appears to have a definitive answer.

And they’re not only merely dead, they’re really most sincerely dead.