Credit: STG Solar

The University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service issued a policy roadmap on planning and paying for the decommissioning of solar facilities, filling a critical gap in information as the clean-energy industry rapidly accelerates across the Commonwealth.

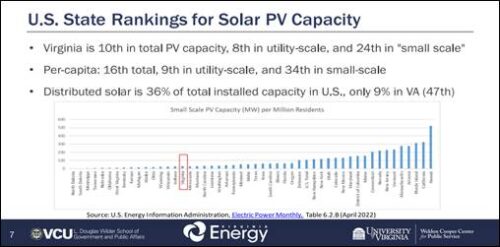

Large- and utility-scale solar facilities are a fast-growing source of electricity in Virginia and a key component of the Commonwealth’s decarbonization strategy. National data indicate that as of June 2022, at least 62 solar facilities produce power in Virginia, with numerous other projects under construction or consideration. Solar is currently the least expensive source of Virginia’s electricity supply and is now generating more power than coal.

But at the other end of the solar boom comes a time when some of today’s facilities retire, in about 30 years, and stakeholders increasingly need to plan for eventually removing them.

In its 60-page report, the Cooper Center provides guidance on the legal, regulatory and financial framework for decommissioning solar facilities, filling a resource gap that was revealed in its Virginia Solar Survey earlier this year, which found the issue to be among the top five topics of interest to localities when it comes to solar development.

“Localities have expressed they need more information about decommissioning in order to feel comfortable that in approving large-scale solar facilities, they are protecting the financial and environmental interests of the community,” said Elizabeth Marshall, senior coordinator of the Cooper Center’s Virginia Solar Initiative. “To date, there has been very little comprehensive research or guidance on the subject, and almost nothing that is Virginia specific. This is definitely of interest to solar developers, localities and stakeholders statewide.”

Marshall added that other states that don’t already have decommissioning guidance may find the report a good model that can be customized as needed.

Decommissioning a solar field by removing the solar panels and support structures is a relatively straightforward process but can come with costs upwards of $1 million. When permitting a large solar facility, localities generally require financial assurance that the installation company will pay for its ultimate removal.

“Choosing the most appropriate form of financial security can be a challenging decision for localities, as it has important implications for the solar project’s construction and financing,” said Irene Cox of the Cooper Center and the author of the report. “We provide several options so that decommissioning is a manageable risk for localities but not an undue burden on developers.”

The report compiles information about state and local laws, recommendations from state and federal agencies, and various approaches in comparable markets to present an inventory of customizable decommissioning best practices. For example, the report suggests localities consider adopting a decommissioning ordinance that, among other things, specifies financial assurance options, conditions for land restoration and post-closure land-use. Ultimately, the center’s report can help protect the financial interests of localities, reduce unnecessary costs to project developers and provide assurance that the land is left in suitable condition.

“Concerns over decommissioning costs can add unnecessary complications to the process of permitting new solar facilities,” said William Shobe, director of the center’s Energy Transition Initiative. “Our new guide should help smooth negotiations over facilities that can be a real asset to the local economy, as well as benefit ratepayers across the state while also helping address climate change.”

News item from the University of Virginia