In markets where consumers face volatile methane prices, MIT researchers propose that increasing installation incentives may be the most effective way to maximize social good and mitigate long-term risks in U.S. electricity markets.

Economists, policy wonks, politicians, and energy professionals often debate the most effective tools for deploying clean energy, with the focus generally on carbon taxes or tax credits. While both have theoretical merits, only one has substantially driven U.S. capacity deployment: the Investment Tax Credit (ITC).

A recent analysis by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research (MIT CEEPR) suggests that in electricity markets like the United States, where most consumers lack long-term fixed-rate contracts and therefore bear market pricing risks, tax credits are the most efficient policy tool.

In the study, Choosing Climate Policies in a Second-best World with Incomplete Markets: Insights from a Bilevel Power System Model, MIT CEEPR researchers propose that a solar ITC exceeding 80% of system costs could optimize policy outcomes focused on social welfare.

A key variable in this model is the price volatility of natural gas (methane), the primary driver of U.S. electricity costs. Recent events in Europe and the United States demonstrate that methane prices can spike due to factors like geopolitical tensions, supply constraints and market practices.

This instability directly impacts all but the largest U.S. consumers, with rising electricity prices exemplified by California’s major utilities. Over the past few years, the state’s three largest utilities have increased retail rates by at least 47%, with San Diego Gas & Electric’s rates surging by 104%.

The MIT analysis indicates that because current market designs place the bulk of price risk on electricity buyers, while power companies can pass costs onto consumers via public utility commissions, front-loaded tax credits could significantly increase renewable energy adoption. This strategy gains importance as the U.S. government aims to sharply reduce emissions.

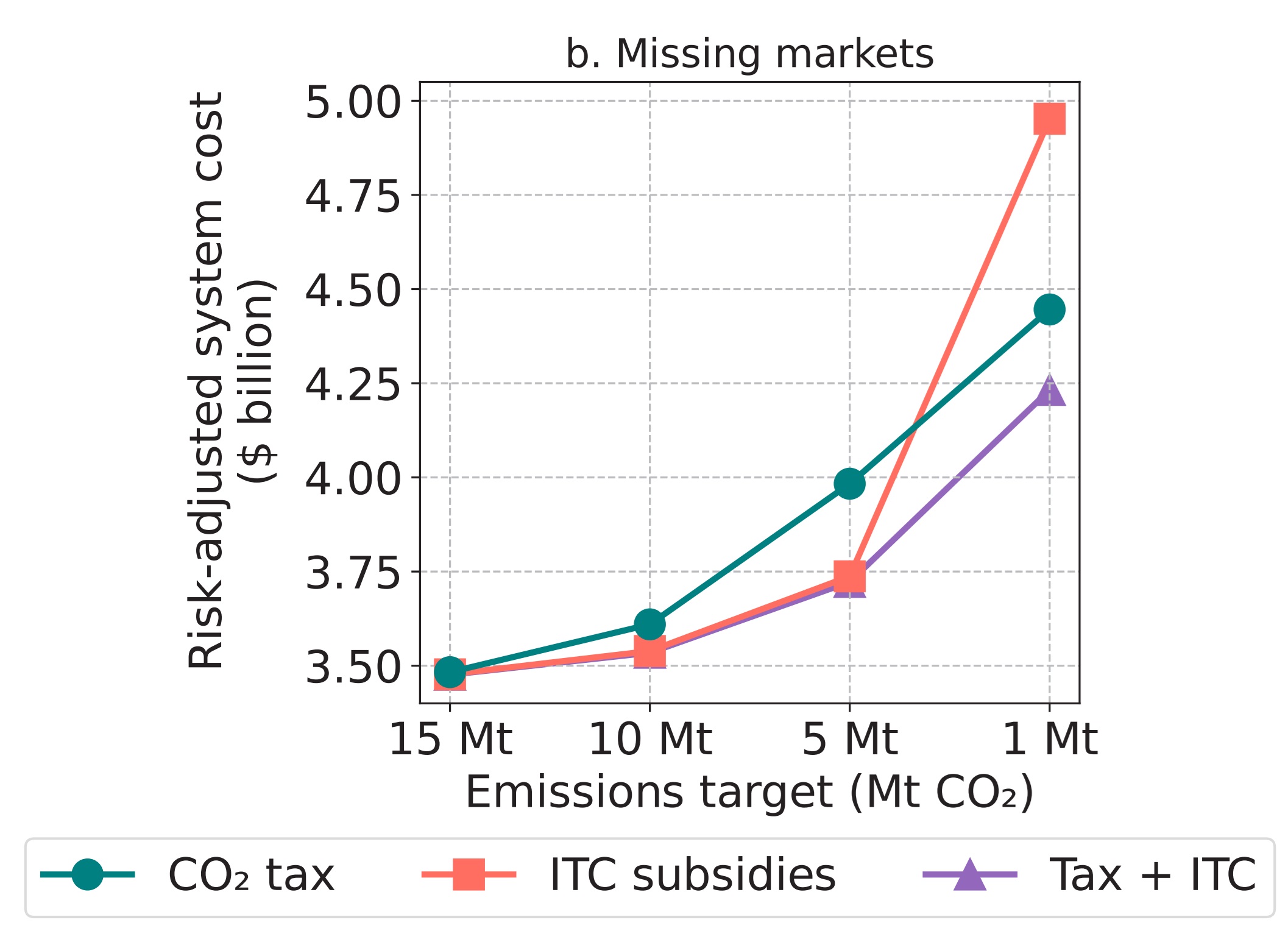

In scenarios with aggressive emissions reductions, (see chart above), MIT’s analysis suggests that an optimal carbon tax could reach $800 per ton of CO₂ emissions, with a solar ITC potentially reaching or exceeding 80% of project costs.

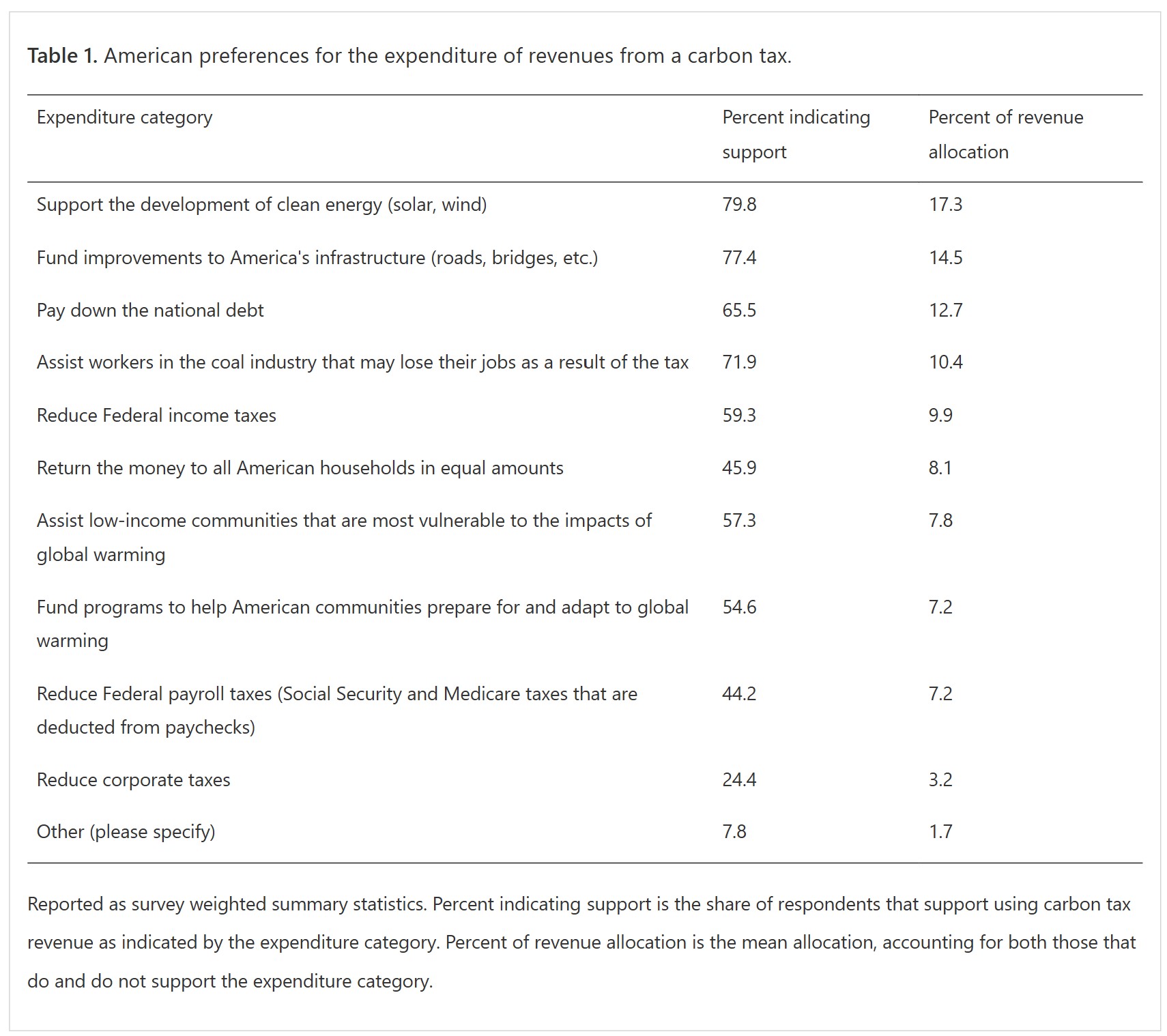

Interestingly, while Americans are generally willing to support a carbon tax, they prefer that the revenue be directed specifically toward deploying new clean energy technologies. This preference suggests that a carbon tax, if designed with public acceptance in mind, would be most effective if directly paired with a tool like the solar ITC.

The paper highlights that market pricing risk exists along a spectrum, with some groups, primarily large technology companies, having access to long-term agreements that stabilize energy prices.

When asked about how this analysis applies to the U.S., where most consumers deal with fluctuating prices, one of the paper’s authors, PhD Candidate Emil Dimanchev, told pv magazine USA:

In reality, market completeness (i.e., adequacy of PPAs and other such contracts) is a spectrum. Reality is in the middle (there are some contracts) and we look at the extremes: full contracting vs. no contracting. This at least gives us the ability to see how power market outcomes change *directionally*. Do we get lower or higher emissions? Do we see more or less investment in clean energy? So essentially this is a cautionary tale that current markets, where investment risk is mostly offtaken by big tech, will not incentivize the high amount of clean energy that governments want to see to decarbonize electricity.

The analysis demonstrates that in complete markets, where all long-term electricity pricing risk is hedged and predictable, a carbon tax is theoretically the most cost-effective policy. However, in “missing markets,” where there is no long-term hedging or fixed contracts, the ITC proves most efficient. In the longer term, as the nation aims to reach very low emissions levels, the study finds that a combination of ITC and carbon taxes would yield the most efficient results.

Popular content