Startup Quino Energy has raised more than $7.8 million to scale up its quinone redox flow battery technology. Harvard University and University of Cambridge researchers came up with the initial research for the battery design.

U.S. startup Quino Energy, a spinoff of Harvard University, said it recently raised $3.3 million from a group of investors led by Japanese venture capital firm Anri. The sum collected through the funding round, which also involved Argentina’s Techint Group, will add to the $4.58 million grant that Quino Energy had previously secured from the US Department of Energy (DoE).

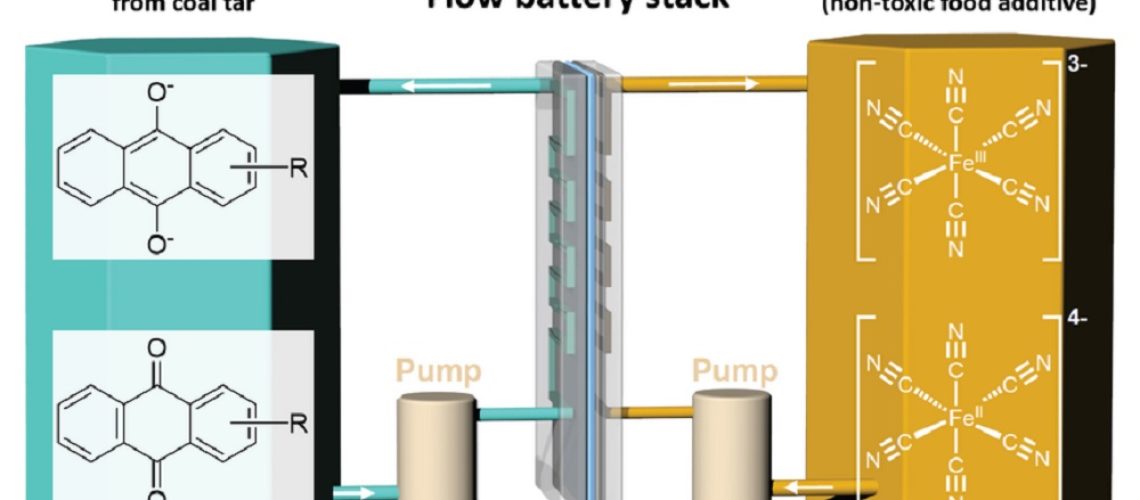

The company said it will use the funds to scale up its redox flow battery technology based on 2,6-dihydroxy-anthraquinone (DHAQ) – or more simply, anthraquinone or quinone.

“Harvard’s Office of Technology Development (OTD) has granted Quino Energy an exclusive, worldwide license to commercialize energy storage systems using the chemistry identified by the labs, including quinone or hydroquinone compounds as the active materials in the electrolyte,” the startup said. “Quino’s founders believe the system may offer game-changing advantages in cost, safety, stability, and power.”

The company designed the battery based on previous research conducted by 16 scientists from the University of Cambridge and Harvard University. Quinone as the active material in the electrolyte eliminates the typical decomposition of chemically unstable redox-active species in redox flow batteries, which is the main factor affecting the storage capacity of such storage devices.

In the redox flow battery, DHAQ decomposes slowly over time, regardless of how many times battery cycles have been performed. When it is in contact with the air, after a cycle, this molecule absorbs oxygen and turns back into its original status.

For this reason, the researchers refer to the molecule as a “zombie quinone,” as it is kind of returning to life after being dead. They said redox flow batteries developed via this approach could offer a net lifetime that is 17 times longer than previous research has shown.

“For grid-scale stationary storage, you want to be able to run your city through the night and when the wind isn’t blowing, without burning fossil fuels. You might go two or three days without wind in a typical weather pattern, and you’ll certainly go eight hours without sunshine, so having a discharge duration at rated power of five to 20 hours can be a very useful thing,” Quino Energy said. “That’s the sweet spot for flow batteries, where we think they can be especially competitive versus the shorter-duration lithium-ion batteries.”