The Midwestern transmission operator MISO is moving to increase transmission and otherwise facilitate interconnection, said a regional trade group leader, yet she also recommended further improvements by MISO and neighboring grid operators.

Lack of transmission is “at the heart” of interconnection problems for large-scale renewables in the Midwest’s MISO grid region, said Beth Soholt, executive director of the Clean Grid Alliance, which represents about 50 industry members. She spoke on a webinar hosted by the nonprofit Clean Energy States Alliance.

Following the MISO board’s approval in July of six transmission lines across nine states, there remains “a lot of work to get all these lines through” each state’s regulatory process, Soholt said. She expects the lines to enter service in the 2028 to 2030 timeframe.

The newly approved lines will support interconnection of 53 GW of renewables, and although they will cost $10.3 billion, they will reduce other costs by $37 to $68 billion, said Johannes Pfeifenberger, a principal with The Brattle Group, in June. Soholt expects MISO to approve a second stage of transmission investments next year, while MISO also considers a third and fourth stage of transmission investments.

Besides adding transmission, MISO has improved interconnection by reforming its interconnection process five times over 20 years, Soholt said, and by informing developers about locations that have transmission capacity available to accept new renewable generation. Another trend in MISO, she said, is using the infrastructure freed up by coal plant retirements to interconnect new renewables.

Solar outpacing wind

“Solar is coming on strong,” Soholt said, in the latest round of interconnection requests announced by MISO in mid-September. Of the 171 GW of interconnection requests newly added to MISO’s interconnection queue, solar projects took the lead at 84 GW of proposed capacity, followed by storage, hybrid, and wind projects. Developers are proposing solar, Soholt said, because with abundant wind generation in MISO, “people are looking to round out their portfolios,” and also because solar can earn a higher capacity credit, as solar has a better profile for meeting resource adequacy needs. Projects in MISO’s queue now total 289 GW, of which 96% are renewables or storage. For comparison, MISO’s peak demand is about 120 GW.

Recommendations

Given that the first stage of MISO’s new transmission won’t be completed for six to eight years, Soholt called for “stopgap measures” such as grid enhancing technologies, which can increase the utilization of existing transmission lines, “to be able to continue to deploy renewables and storage.”

Regarding interconnection studies, Soholt called for “some kind of reconciliation” when a grid operator misses interconnection study deadlines.

Another key challenge, she said, “is the operating assumptions that MISO has been using” when conducting an interconnection study for storage resources. She called for MISO to “look at how storage is going to operate” and recognize that storage can “be a solution.”

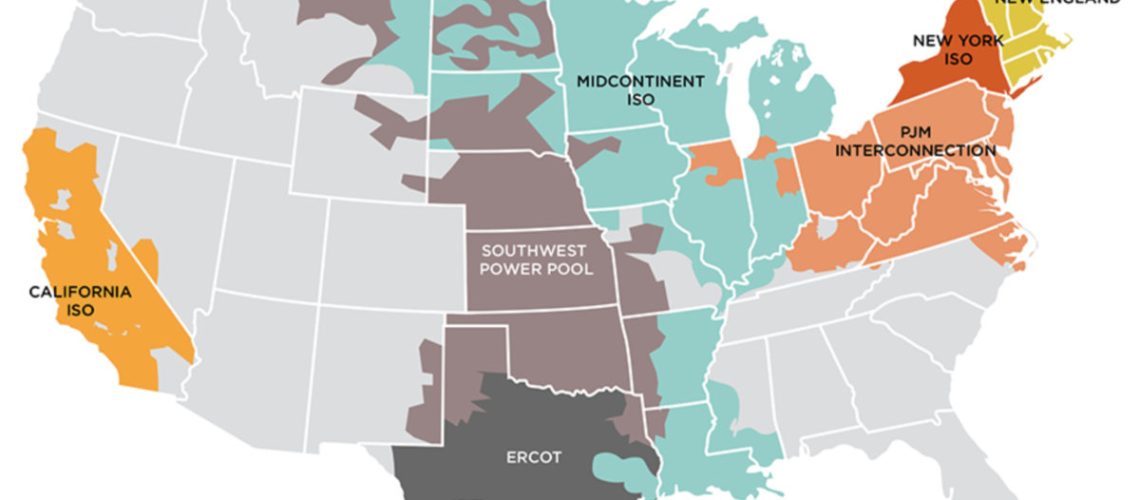

Another factor that is really slowing down interconnection is the slow pace of affected system studies, according to Soholt. She explained that neighboring grid operators SPP and PJM need to study impacts to their systems for MISO-located new generators, especially along the seams, or grid region boundaries. “They have been even slower than MISO,” she said. “There are some efforts underway to try to fix that,” she added, with SPP and MISO conducting a joint targeted interconnection study, in which cost allocation will be a major factor. “We’ve got to get something going on the PJM side.” Cost allocation within MISO is also a “major challenge,” she said.

With MISO’s currently constrained transmission, the “sheer number of megawatts” in the interconnection study groups “require very large transmission solutions to solve,” Soholt said. As a result, “the models can run for days trying to search for an answer.”