California has multiple crises in its electricity sector. Electric utilities are under legal obligation to deliver on four key aspects: to render adequate, impartial and reasonably efficient service at reasonable rates to all ratepayers. Yet, the state’s investor-owned utilities are dealing with mounting struggles on each of these obligations.

First, on adequacy, the state has challenges with mounting demand due to the electric vehicle boom and home electrification. Pacific Research Institute warns that the state may fall 20% short of its electric resource adequacy needs by 2045 as EV charging adds an unprecedented load on the grid.

Second, on impartiality, the state’s Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) approved utility requests to assess a monthly fixed charge on its customers, regardless of how much electricity they use, and it is double the national average and is graduated based on income levels. While the Income Graduated Fixed Charge (IGFC) was pitched as an equity-focused change, analysis has shown that it may disproportionately harm Californians with low electricity bills.

The third feature requires the system to be reasonably efficient. However, California’s investor-owned utilities as structured have a disincentive to spend efficiently or create an energy-efficient system. The more capital utilities spend on infrastructure, the more they can get rate increases approved.

And the fourth legal requirement, providing reasonable rates to all ratepayers, has been a failure in recent years. The state’s electricity rates have exploded in the last three years, far outpacing inflation. PG&E was approved for a 13% rate increase this year, and along with the IGFC, which will average about $24 for most customers in California, affordability has been challenged. What’s more, the IGFC approval was not capped, meaning utilities have open season to continue tacking on higher fixed charges.

Utility filings show that over 20% of customers of the three large utilities are over a month late on their bills, and that number rises to 33% in low-income brackets. Meanwhile, PG&E posted record profits in 2023, growing 25% year-over-year to $2.2 billion.

Virtual power plants

There is no silver bullet for meeting the challenges of modernizing the grid, moving on from fossil fuels, and ensuring California’s utilities meeting their legal obligations to serve adequate, impartial, reasonably efficient and reasonably priced electricity. But there are some improvements to be made, and according to a report from the Brattle Group, virtual power plants (VPP) can be an impactful improvement.

VPPS can help California save $750 million per year on electricity while advancing clean energy adoption, increasing electric reliability and efficiency, said the report.

A VPP is a virtual aggregation of small-scale, distributed energy resources (DERs) including rooftop solar, energy storage, electric vehicle chargers, and demand-responsive devices such as water heaters, thermostats, and appliances. In a VPP, customers typically enter an agreement to reduce electricity consumption or dispatch stored electricity from solar-plus-batteries during peak demand events.

Over the last decade, the U.S. has spent more than $120 billion on 100 GW of new generation capacity, mainly for resource adequacy. Brattle Group estimates nationwide utilities could save $35 billion by 2033 by focusing on VPPs for serving peak demand on the grid.

For California, serving peak demand has become a critical issue. Currently, in the evening when solar production goes down and residents are returning home from work and using more power, demand spikes.

The mismatch of supply and demand is represented by the “duck curve” which has been deepening in California through recent years, causing cost and adequacy issues. Brattle Group reports that the cost of resource adequacy has doubled in California since 2017.

Peak demand is often served by reserves of natural gas generators in small power plants called “peaker” plants. Peaker plants are among the least efficient and most polluting resources serving the grid today.

Brattle Group’s said VPPs can immediately go to work as an alternative to dirty peaker plants. By 2035, California’s VPP potential would exceed 15% of peak demand, said the report. This would represent the deployment of more than 7.5 GW of flexible VPP capacity, or about five times the current VPP capacity across the state.

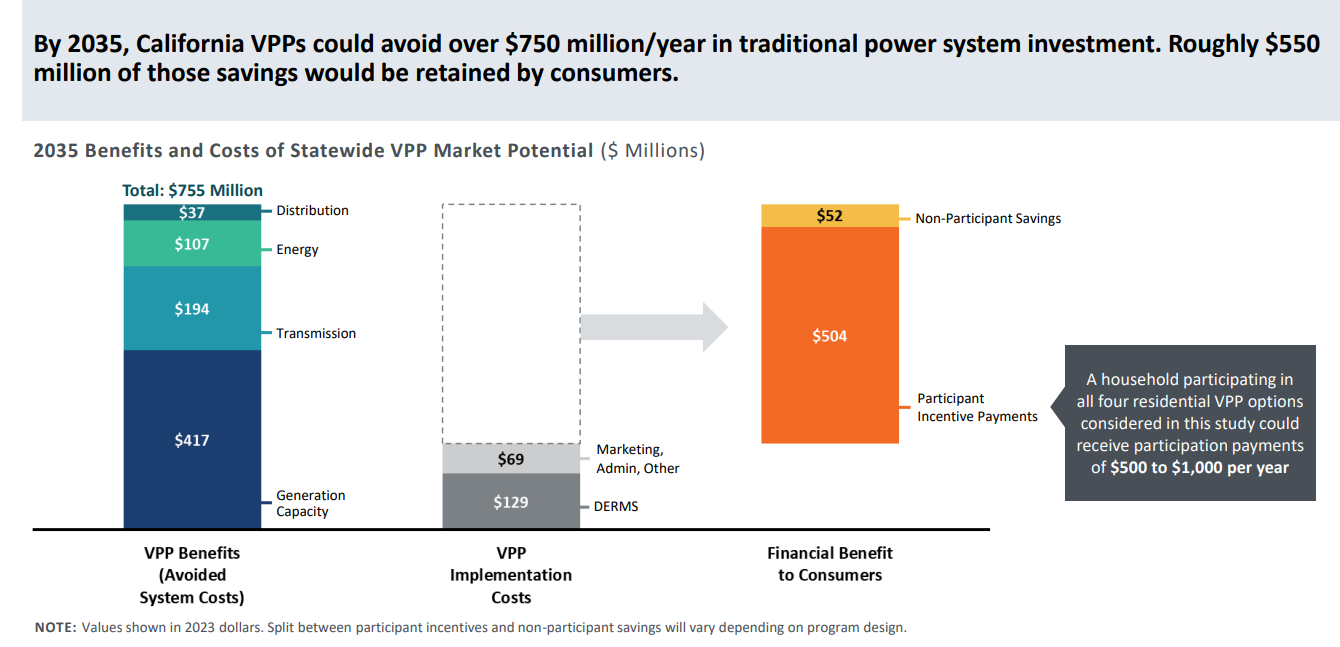

This level of deployment would help save $750 million per year, according to Brattle Group’s analysis. This would break down to annual savings of $37 million in distribution, $107 million in energy costs, $194 million in transmission, and over $417 million in avoided costs from building new inefficient generation capacity.

Most of these savings could be passed on to customers, said Brattle Group. Of the $750 million in savings, just under $200 million would be needed for implementation of distributed energy resource management systems to operate the VPP, as well as marketing and administrative costs to launch the program and reach customers.

The remaining roughly $550 million in savings would be passed on to customers. Participants in VPP programs would agree to dispatch power from their solar and batteries, their electric vehicle battery, or reduce electricity consumption during peak hours. In turn, these program participants would be paid about $500 to $1000 per year for pitching in to help smooth out demand in their local grid. A further $52 million per year could be paid to program non-participants, said Brattle Group.

“California already has a 7,000 MW load shifting goal, as well as load management standards that could facilitate VPP uptake. New draft legislation effectively could establish the equivalent of a renewable portfolio standard for VPPs across the state,” said Brattle Group.