Ethanol emits more greenhouse gasses than the gasoline it is supposed to replace. Additionally, ethanol (corn) farms greatly under-utilize one of the greatest resources we have – land.

Of the ~92 million acres of corn planted in the US each year, roughly 40 million acres (1.6% of the nation’s land) are primarily used to feed cars and raise the octane of gasoline. If this land were repurposed with solar power, it could provide around three and a half times the electricity needs of the United States, equivalent to nearly eight times the energy that would be needed to power all of the nation’s passenger vehicles were they electrified.

However, if we were to transition this 40 million acres are of fuel to solar+food (agrivoltaics) – we could still meet 100% of our electricity needs, and power a nationwide fleet of electric vehicles.

Recent research from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory suggests that utility scale solar power in the United States generates between 394 and 447 MWh per acre per year. (For this document we’ll assume a more conservative 350 MWh/acre)*. Thus, just one acre of solar panels provides enough energy to propel America’s most popular electric vehicle – the Tesla Model Y – nearly 1.3 million miles each year.

In a good year, one acre of corn is expected to generate around 328 gallons of ethanol. Since ethanol contains only ⅔ the energy of gasoline, a comparable crossover SUV averaging 30 miles per gallon would travel only 6,600 miles per year on that acre of corn.

That’s not a typo. solar panels produce roughly 200 times more energy per acre than corn. This striking figure makes an ironclad case in favor of converting vehicles to electricity – and that’s before we take into account the environmental and health benefits which would result from the profound reduction in emissions.

The ‘recent’ news that US ethanol emits 24% more emissions than gasoline, is in fact old news. Politics in the United States, influenced by agricultural industries, fossil-fueled fertilizer manufacturing, and perhaps a well-intentioned ulterior motive of underwriting food for national security, has led to a massive subsidy program for corn growers.

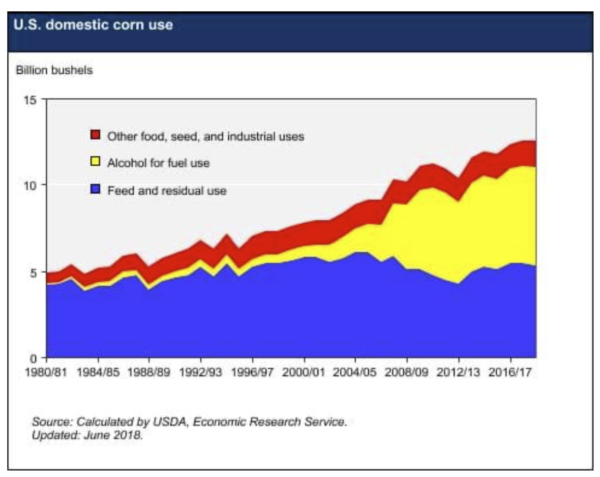

In fact, since 1980, pretty much all of the additional acres used to grow corn have gone towards fueling vehicles, not humans. We need not point fingers at farmers – they simply produce what the market demands. But these demands, which our civilization imposes on our soil, have resulted in far-reaching consequences.

Corn is particularly adept at siphoning nutrients from our soils. Restoring these nutrients requires fertilizers sourced from fossil-fuel feedstocks and produces more CO2 emission than any other human-driven chemical process on earth. Meanwhile, solar can help alleviate our nitrogen-fixation emissions crisis as well, by pulling fertilizer out of thin air.

With these factors in mind, we propose a new national security initiative – one that combines solar electricity generation with food production in order to solve many issues in one fell swoop. We urge landowners, developers, and legislators to prioritize the replacement of ethanol field corn with agrivoltaic operations. These operations should specifically target locations with the highest risk for fertilizer runoff. It’s time to bring our agrarian society into the 21st century.

And, just for the sake of fuel security, let’s incorporate some hydrogen generation into the picture as well.

#AgrivoltaicsforEthanol

Forty million acres of ethanol field corn could be used to generate 14 petawatt hours of solar electricity, if deployed in standard, highly efficient installation techniques. A reminder – that’s 3.5 times more energy than the current U.S. electricity consumption.

However, that is not our goal.

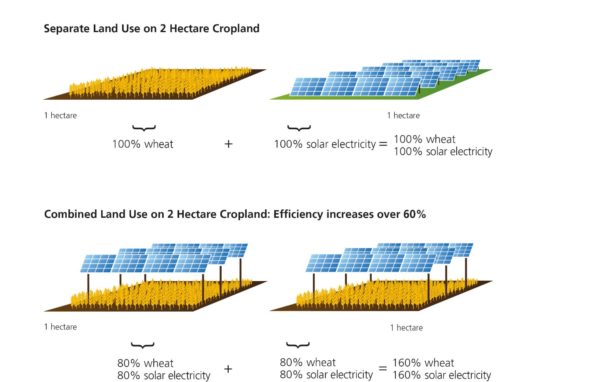

Even though we’re still in the nascent stages of agrivoltaic development, it’s fair to say that solar plus food facilities will generate at least half the amount of electricity per acre as we leave space for farming machines. One analysis from Germany found potatoes could be grown at 80% of their initial volume, while electricity could also reach 80% of its potential.

In the scenario where we only get 50% of the solar output from the land, our repurposed acres would generate around 7 petawatt hours of electricity per year. That’s eight times the amount of electricity required (~0.88 PWhrs/year) to push 3.26 trillion passenger car miles in the US every year, and enough left over to electrify the nation 1.5 times over.

Of course, we don’t need (or probably want just yet) to power the US only via solar power. Thus we suggest powering the nation with only 50% solar – thus setting our electricity for our cars and our general power use around 16-21 million acres.

If we’re going to be honest about electrification, we must admit to ourselves that the 40 million acres of corn we blend with our gasoline is obstructing this path. But if we want to support our farmers, while generating massive amounts of local, secure, clean – and as sure as the sun rises – predictable electricity pricing, we must consider trading our ethanol for agrivoltaics.

#AgriovoltaicsforEthanol

*There are several caveats to this article.

For instance, this author’s interpretation of the solar capacity and electricity per acre per year research is on the higher end of the estimations (currently), as the research quoted focused specifically on land used for solar power – but less so on the land supporting the solar. One estimation from a respected modeler suggested we use a value of 220 MWh/acres/year – 37% lower than this article’s 350 MWh/acre/year, and roughly one half of the 447 MWh/acre/year value in the research paper quoted.

Another debate is the exact number of acres should we specifically say are ethanol acres – this is something researched by many, and can change based on the source.

Additionally, many questions related to energy storage scaling, high voltage power lines deployment, scheduling the charging of EVs, energy losses in charging/discharge, and whether or not to use solar energy to generate and compress hydrogen remain. Many paths are possible, but first we must eliminate the archaic notion that corn acreage is sacrosanct.