Some of the most enduring images from the Los Angeles riots are the photos of armed Korean shopkeepers patrolling the rooftops of liquor stores and laundromats to deter rioters.

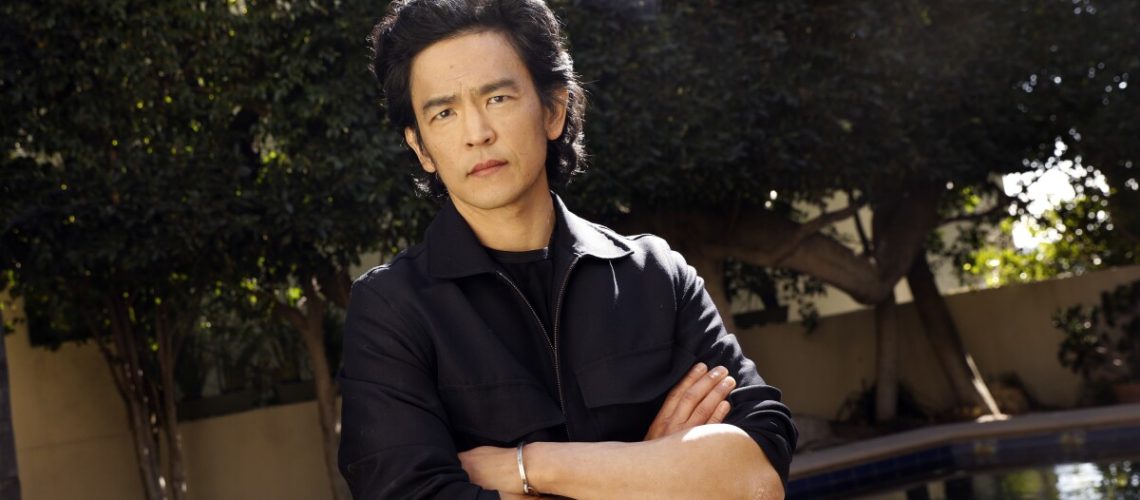

In some Korean Americans those images inspire pride, and in others, shame. The actor John Cho, he told me, felt mostly panic and fear. Then 19 years old and a student at UC Berkeley, he could see how the images were being interpreted and worried that they would spark more hostility toward Koreans.

In his new young adult novel that he wrote with Sara Suk, “Troublemaker,” his goal was to start with those photos, and zoom out.

“We wanted to start at that stereotypical image of the rooftop Koreans. Our thinking was, ‘What if we could humanize this person? What would that look like?’”

Though written for a young adult audience, Cho’s novel is a sincere attempt to make sense of an event that we are still trying to understand. This year is the 30th anniversary of the Los Angeles riots, and though we are still trying, I don’t think we have fully made sense of what happened. In 2017, for the first time since the riots, a Loyola Marymount University poll found that 6 out of 10 Angelenos surveyed believed that another uprising is likely within the next five years.

Cho doesn’t see himself as an expert author or historian on the subject. But now, at 49, he is a father too, wrestling for the words to explain an event that his own parents have always discussed in hushed Korean behind cupped hands.

So last summer, as the George Floyd protests broke out and anti-Asian violence was on the rise, Cho decided to write a book about the Los Angeles riots. He describes it as the book he wished his younger self could have read.

The novel follows a young Korean American boy named Jordan trying to reach his father, a liquor store owner, on the night that the riots break out. His goal is to deliver a gun he found at home to his father, so that he can help protect the store. The narrative locates itself around the violent chaos of that night, but never inside of it, turning down the volume to focus on the relationship between Jordan and his father.

On his journey, Jordan meets a Black neighbor who helps bandage his cuts, and a Mexican gardener who helps him out with a ride. When he finally reaches his father, they have a conversation that could only exist in fiction. It was a conversation that Cho and his father, a Korean American pastor in Glendale, have had in bits and pieces over the years, and Cho decided to fill the blanks in.

In it, Jordan’s father apologizes for calling him a disappointment and shares his concern that coming to America may not have been the best decision. He tells Jordan that he’s hard on him because society will not look out for Koreans. And he refuses the gun, rejecting the idea that violence should be responded to with more violence.

“When I heard what happened to Latasha Harlins,” his father said, “I realized, things aren’t different after all. People will make a lot of terrible choices in the name of protection.”

When I read the book, I found myself comforted by the idea of a Korean American shopkeeper and war veteran who has learned the futility of violence. I was deeply moved by the mere idea of an immigrant father who has a heart-to-heart conversation with his son.

Fiction can give us the closure that reality does not have, especially around the events of 1992. In Cho’s story, different races can see past conflicts and help each other. The L.A. riots become a fable about the futility of violence. The scales of justice rebalance themselves, and families and neighborhoods are brought closer together instead of further apart. With this reinterpretation of the past, it becomes easier to imagine a better future.

Growing up in the aftermath of the riots, traumatized by the sight of emergency lights and sirens abandoning Koreatown, Cho’s parents taught him to be wary of the outside world. Expect disrespect, insults and injustice, and overcome them.

“It was, tighten up your abs and get ready to get punched when we went out there,” Cho said to me on a previous episode of The Times’ Asian Enough podcast.

It was a childhood that left Cho feeling cynical and alienated. It taught him to keep his guard up as an Asian American actor trying to navigate Hollywood racism, and to keep a smile on his face as he clenches his fist in his pocket.

But that’s not what he wants his own son to learn, Cho said.

“I would have liked a book that spoke to me honestly about adult events,” Cho said. “My kids are curious, and we have to help them understand what’s happening in their world. It’s a fantasy that we can compartmentalize those things.”

If the riots had one main impact on his family, it was a sense that you had to assert belonging rather than wait to be awarded it, Cho said.

“There was this shift,” Cho said. “It was like, ‘We spilt blood here, now this is our land, too.’”