By the decade’s end, data centers in the United States are projected to account for as much as 35 GW of demand and about 9% of the country’s electricity consumption. Though these are merely forecasts, to power the 24/7, 365-day operations, utilities plan to finance dozens of GWs worth of new generation resources from clean energy to natural gas.

According to a Goldman Sachs study, natural gas could supply 60% of the expected data center demand. This significant increase in gas is reflected in many utility integrated resource plans, including Dominion Energy in Virginia, which wants to build more than 2.9 GW of new long-term gas capacity in the next 15 years as a short-term solution to load increase. Some utilities have also resorted to proposing new payment structures in addition to planned generation resources. AEP Ohio proposed a unique tariff structure that, if approved, would require new large-capacity data centers to pay for their own transmission needs, and Duke Energy is considering contract agreements for data centers that would require them to provide upfront financial contributions to construct new generation resources to help power them.

Besides natural gas, nuclear is also seen as an option to power data centers, with various developers and data companies already examining this alternative. For example, Oklo, a California-based advanced nuclear company, has committed itself to providing its clean energy solution in response to increasing demand for AI adoption and data centers. The company announced a non-binding partnership in late May with Wyoming Hyperscale, which wants to use Oklo’s microreactor design to power a state-of-the-art data center campus using 100 MW of nuclear energy. As for data-heavy companies, Amazon Web Services bought a 960 MW Cumulus data center campus in northeast Pennsylvania in early March that will be powered by the 2.5 GW Susquehanna nuclear power plant. Nevertheless, with the construction price for compatible small modular reactors (SMRs) rising and SMRs and microreactors still far from commercialization, this reality may not come to fruition anytime soon. Plus, if new large-scale reactors are considered, the estimated $7.6 billion cost to ratepayers of the now-operational Vogtle Units 3 and 4 – which increased residential rates by about $9 a month – might dampen the prospects of nuclear as an option as well.

Either way, new resource proposals will persist as artificial intelligence and other significant data sources enter the equation as a catalyst, partly because heavy-data users like Google are experimenting with technology like AI-infused internet browsing. For context, compared to a Google search that consumes approximately 0.3 Wh per request, a single AI-powered Google search request may even consume about 23x to 30x more than, according to worst-case scenarios and research estimates published in late 2023. It is important to note that these estimations are dependent on a number of factors staying the same, including the availability of AI-based chips and the 24/7 operations of data centers at max capacity. However, as data center efficiency grows and operation procedures change, these estimates will shift.

Moreover, while the national impact of data centers is expected to take up a significant chunk of the nation’s overall electricity consumption, the most significant ramifications will be seen on a state-to-local level, especially as growth continues to concentrate in specific pockets of the country. State by state, Virginia is far ahead in the number of current data centers. The northern part of the state is considered the nation’s most significant data center market, even the world, with 35% of the globe’s hyperscale data center share – a type of data center facility that typically supports the business activities of massive data-driven companies like Google, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft, just to name a few. The state legislature has responded by introducing bills this year to limit the provision of sales and use tax exemptions to only centers that demonstrate certain energy efficiency requirements, requiring localities to assess the grid impacts of proposed center sites, and disallowing utilities from recovering costs through their customers from electric grid infrastructure that mainly services the load coming from data centers.

Other state responses have been more mixed in their reaction, with Massachusetts – a state with about 50 data centers – introducing legislation courting new centers with a sales and use tax exemption, Michigan pushing forward with an extension of their existing data center tax exemption until mid-century, and New York – with almost 130 data centers – wanting to create an energy benchmarking program to account for high-energy infrastructure.

While the legislative and utility actions mentioned address the potential grid and energy impacts of data centers, they also touch on the future downstream cost issues associated with a utility’s response to the massive amount of incoming load growth and the capital recovery that customers, especially those that are low-income, will have to deal with.

Map of energy consumption from data centers in states with significant 2023 load. Data center consumption data depicts the highest-growth scenario states are projected to see in 2030 relative to total electricity consumption. Data Source: EPRI

Low-income load bearers

As utilities attack the projected data center load growth issue with additional investments and emerging technological applications, the customer is positioned to help subsidize the cost through rate increases as part of these utilities’ cost recovery processes. In the case of Duke Energy in North Carolina, the utility can recoup about 10% from new construction.

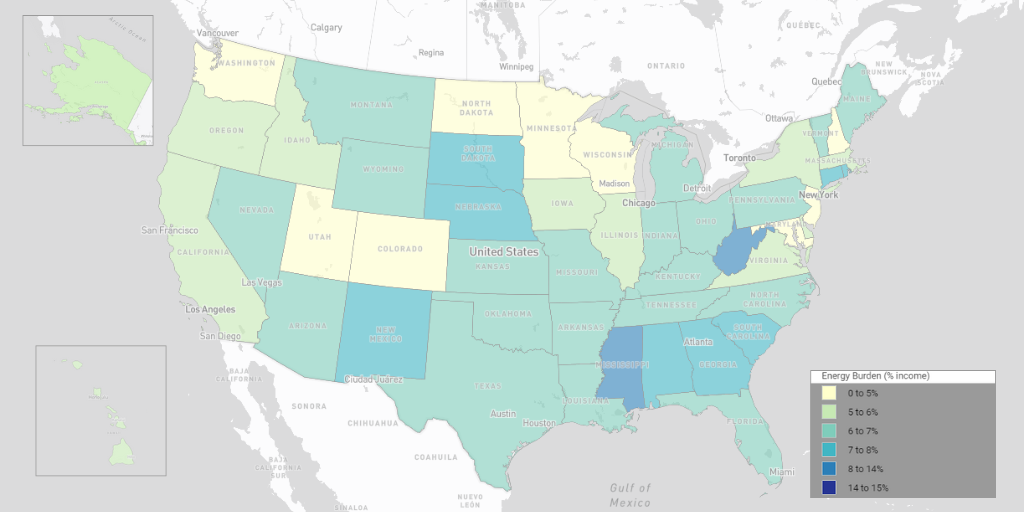

However, while wealthier households have the financial cushion to protect themselves from these rate increases, low-income customers do not, so the weight of frequent or significant bill increases bears greater financial struggle. The lack of financial security for low-income households is exemplified by one’s energy burden. In the United States, the national average energy burden, or the percentage of gross household income spent on energy bills, for low-income households is 6%, according to the Department of Energy’s Low-Income Energy Affordability Data (LEAD) tool. This average is based on an estimated 51 million households that identify as low-income, which is about 42% of all households in the country.

Depending on a person’s locality and household income, the energy burden can even be higher than 30%, particularly if you live in the Southeast. Even the financial toll from trying to keep cool during the summer heat can spike a household’s energy burden, which the National Energy Assistance Directors Association (NEADA) and the Center for Energy Poverty and Climate (CEPC) reported will increase by 7.9% this year. With the expected increase in utility bills in the coming years, such a high and localized energy burden rate may become more widespread and prevalent.

Low-income utility bill assistance

Since the reality of the energy burden in the country is not a new phenomenon, there are a number of financial assistance programs and approaches that the federal government, states, and investor-owned electric utilities have either implemented or are currently examining as options. For example, modeled after Maine’s “Project Fuel” program and created in response to the OPEC oil embargo in the early 1970s, the federal government established the Emergency Energy Conservation Program later in the decade to provide weatherization-focused assistance and eventually direct bill assistance for low-income households. It was one of the earliest programs of its kind. It would end up turning into what is now known as the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), operating in every state, the District of Columbia, and most tribes and territories, to prevent energy-bill payment emergencies by providing payments to fuel suppliers/utilities and/or households.

Map depicting the national energy burden distribution for low-income households based on state median income; Source: U.S. Department of Energy Low-income Energy Affordability Data Tool

LIHEAP is commonly used to determine income eligibility for several other state and utility assistance programs. However, access to the federal program has been severely limited. Federal funding for fiscal year 2024 was cut by $2 billion compared to 2023, reducing the number of low-income households served by 1 million in addition to the program’s benefits. Because of the severe budget fluctuations that each state program faces due to federal decision-making, state and utility assistance programs are critical to help fill in the gap and then some.

Many additional state and utility programs exist and vary in terms of approach and scope and can take the form of an income-based discount, a percentage of income payment plan (PIPP), and an income-graduated fixed charge, among other types of payment assistance, like late payment fee and utility shut-off exemptions. Income-based discounts entail a utility or a state providing a continuous or one-time payment attributed to an income-eligible customer, either removing the mandatory fixed charge from a bill or providing a percentage reduction of the overall monthly bill according to a specific income range, among other offers.

Then, there are PIPPs, which refer to income-specific payment plans that allow certain customers to pay only a portion of their utility bill based on a percentage of their overall income. Existing PIPPs vary in terms of their price cap. Still, no program in the country inches above 10% of a household’s income, and some programs may also determine percentage payments based on the primary heat source, electric or otherwise. This payment plan is comparable to a student loan income-driven repayment plan. It can be a helpful tool to limit a low-income household’s monthly energy expenditures and allow households to dedicate a higher share of their disposable income to pay off other bills and to put food on the table, or perhaps allow a household to establish and/or grow their savings.

There is also the income-graduated fixed charge approach, which has only recently been implemented in California. This novel method of equitable ratemaking mirrors progressive taxation, in which the lower your income, the less you must pay, and is a significant departure for investor-owned utilities in the state impacted by this change, which did not impose fixed charges before this.

Part Two of this blog will look at the utility perspective on equitable ratemaking.

Justin Lindemann is a policy analyst at NC Clean Energy Technology Center.

This article originally published by NC Clean Energy Technology Center. Click here to learn about our DSIRE Insight subscriptions, custom research, and consulting offerings on various clean energy technologies for interested individuals or organizations.

Popular content