The United States has several good reasons to hold off on new import tariffs: the Inflation Reduction Act, China’s high solar competency, U.S. prior commitments to grow its solar fleet, and the shift of solar manufacturing from China to new nations.

The Department of Commerce is expected to make a ruling on whether to apply anti-circumvention tariffs against four countries in southeast Asia on December 1. The complaint notes that Chinese companies sought out new countries to manufacture their goods in an attempt to evade tariffs levied against their products.

It’s well known that part of China’s national growth strategy is to strategically acquire technologies – via theft, if necessary. The Obama administration kept a lookout for bad actors, and ended up charging members of the Chinese military with computer hacking and espionage.

China has made solar electricity generation a key piece of its growth strategy. This includes strong subsidies for certain Chinese companies anointed by the state. Those companies then sell – or dump – heavily discounted products around the world.

As a result, there have been multiple instances where tariffs have been slapped on solar panels originating from China. During the Trump administration, nearly all solar panels originating from foreign countries received an import tariff.

Whether or not tariffs have ever worked to increase domestic production is a question of folklore. Data clearly shows that the USA saw paltry amounts of solar capacity growth preceding the Inflation Reduction Act. Immediately after the IRA act was signed, the industry was booming. Companies like Qcells began establishing the world’s largest vertically integrated solar module facilities.

For manufacturers, carrots are producing better results than sticks.

This begs the question: Should the United States add new import tariffs? I would argue that we should thread the needle. While we should not accept materials from geopolitically sensitive areas of China, and though we should maintain tariffs against materials from China’s mainland, we should not add new tariffs to global supply chains, for the following reasons:

- China’s solar manufacturing is exceptional, producing record efficiency HJT solar cells. If the US wants to make use of this technology, we cannot lock out these products.

- The IRA will push US manufactured module costs below 10 cents per watt – these manufacturers will need some price competition.

- The United States must install 100 GW of solar panels per year in order to meet our clean electricity goals.

- Pushing China to manufacture solar panels outside of its mainland – and away from politically sensitive areas – is geopolitically beneficial to China, and to the nations that would host China’s manufacturing, and to the globe.

First, China’s decision to make solar power a part of its Five Year Plans has driven the resource to its current amazing growth rates – with Longi suggesting 1 TW a year being installed by 2030.

Current projections suggest that if we account for emissions alone, electricity generation is on pace to meet our clean energy goals. Meeting our domestic goals would not have been possible if it were not for China’s acceptance of economic losses from financing solar factories in a market where the product’s price was falling precipitously.

By taking on the challenges of manufacturing several billion solar panels, China made itself a technological leader. Chinese companies have significantly advanced polysilicon technology and solar module efficiencies. Longi and Jinko have repeatedly broken each other’s efficiency records, showing how technological advancement in China’s solar industry is both persistent, and reliable.

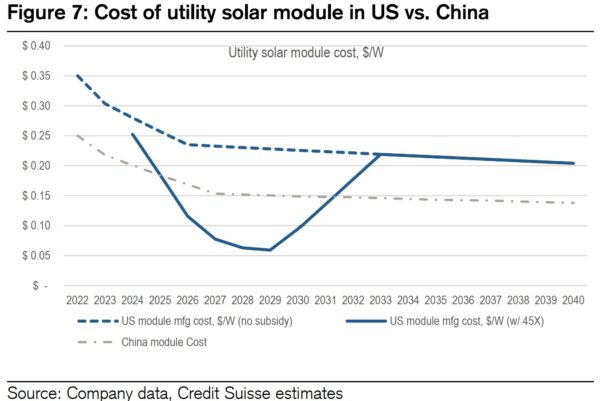

Another reason to avoid tariffs is that our own budding domestic manufacturing boom may very well need competition from highly experienced overseas manufacturers, like the Chinese. We need manufacturing competition from China because they’re the world’s best, and they will push U.S. manufacturing to stay focused on delivering high quality goods to the American market. An analysis by Credit Suisse suggests that solar module costs could fall to almost a nickel per watt, on average. This author posited that First Solar products might essentially cost nothing to make, after tax credits are applied.

In order for these benefits to truly flow from the IRA to the American people (and not just to corporations – many of which are foreign companies), our manufacturers need to know that there’s a beast breathing down their neck. Global competition is essential, because it keeps domestic pricing and quality in check.

Projections have suggested that an aggressive tariff might mean that imported module pricing could hit 50 cents per watt. If that happens, foreign products will essentially disappear from the U.S. utility scale market, introducing an opportunity for highly incentivized U.S. fat cats to get lazy.

When it comes to installing clean capacity, some have suggested that we are on climate war footing – and that doing anything to hurt ourselves would be foolish. Removing so much product from the market could spite the United States, right when we need it the most.

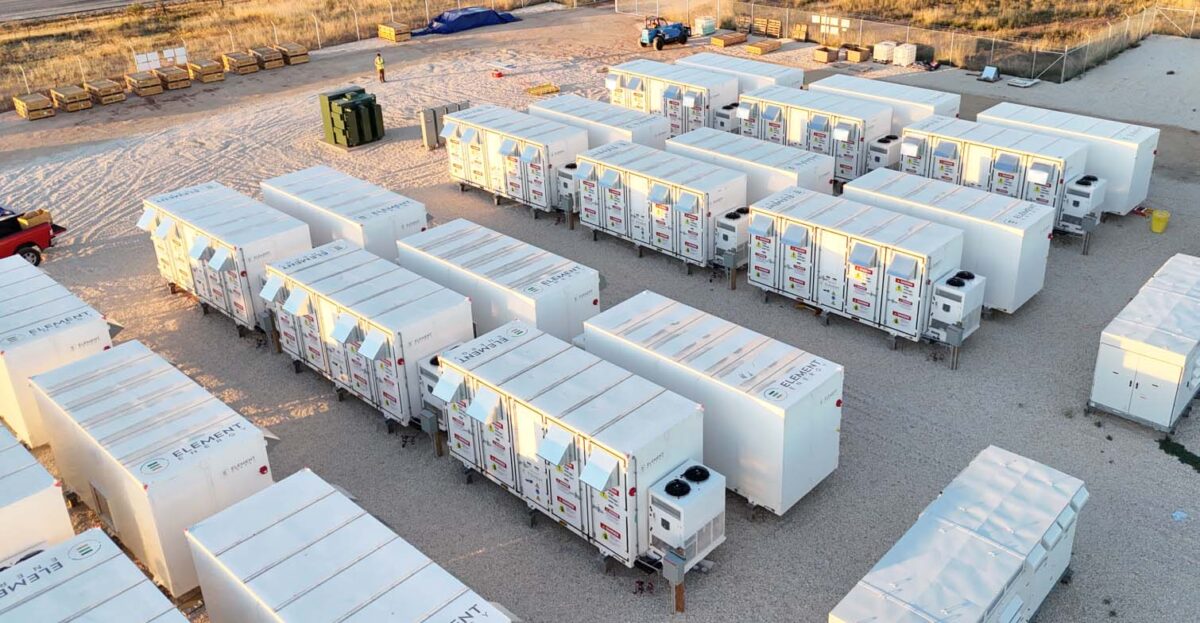

The Biden administration seeks to deliver 40% of U.S. electricity from solar power by 2035. Reaching that goal will require hundreds of gigawatts of capacity – peaking at over a hundred gigawatts per year in the 2030s.

Although we have heard many announcements of domestic solar module manufacturing facilities, at this moment there is no path for the U.S. to manufacture all 37 GW of the capacity slated for 2023, not to mention the projected 75 GW for 2027, or 105 GW for 2029.

Take note: The aforementioned Credit Suisse report suggests that the IRA might turn the U.S. into a net exporter of solar modules. If the U.S. were a net exporter and subsidizer of solar modules, would our call for import tariffs really be… honorable?

Finally, geopolitically speaking, there are benefits to threading the needle when it comes to politics with China. While the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act has had little effect on American solar panel manufacturing, the current mainland solar tariffs did prompt China to move its solar supply chain globally.

Naturally, global attention on western Chinese actions has pushed solar manufacturing out of the region and into the rest of the world, into nations that should benefit from the added jobs and technological development. If our species can work together a bit more, by putting pressure on ourselves to be better to our neighbors, we will see incremental benefits.

There will be many complex considerations to be made as our nation moves forward with its energy resources on this aggressive planet. These anti-circumvention tariffs represent a small, but important, moment of inflection.